THE FOUR EDITIONS OF THE ‘MEMORANDUM ON THE EARL OF ELGIN’S PURSUITS IN GREECE’

In 2002, my dormant and somewhat uninformed interest in the so called ‘Elgin Marbles’ was awakened by the writings of Professor Epaminondas Vranopoulos, who in turn was interested and angered by an anonymous Memorandum used to support Elgin’s bid to sell his collection to parliament, which began in 1810.

I had always thought of the Elgin Marbles solely in terms of the removal of structural and decorative marble masonry from the Parthenon temple and was surprised by Professor Vranopoulos’s details of grave robbery taken from Elgin’s memorandum. My curiosity aroused, I decided to see if I could track down a copy of the “rare book” that had ignited the Greek academic’s anger.

‘The Earl of Elgin’s pursuits in Greece’; rare book, sales catalogue, PR spin or what?

My online Google search in 2002/3 drew a blank (a search now would show many hits), but a search of the online catalogue of the National Library of Scotland (NLS) showed they had three copies of the ‘Memorandum On The Earl Of Elgin’s Pursuits In Greece’, which they had inherited when the library had been gifted the collection of the Faculty Of Advocates in 1871. The authors were given as Bruce, Thomas; Hamilton, Richard William and West, Benjamin. I copied the three editions.

These three editions from the NLS were added to by a copy from a German university I found online, so I then had four copies to study.

My studies of the, almost identical editions of this publication, led me to conclude that the anonymous Memorandum had been written, in the main, by none of the above stated authors, but by Dr. Philip Hunt (Hunt), who was the chaplain and occasional private secretary of Thomas Bruce, the Seventh Earl of Elgin (Elgin).

I didn’t come to this conclusion lightly, as I didn’t want to disagree with my hero, Prof. Vranopoulos, but could only see one author after examining letters that Hunt had sent to Elgin’s mother in law, Mrs. Mary Hamilton Nisbet, while he was imprisoned in France with Elgin in 1805.

Hunt had formed a close attachment with Mrs Hamilton Nisbet when she had visited her daughter Mary, Elgin’s wife, in Greece in 1801 and in his writing he appeared to be trying to flatter Elgin’s mother in law and present her son-in-law (his employer) in the best possible light.

I congratulated myself that as a layman, with only a very basic education, I had been very clever in disproving the theory of an eminent Greek academic as to the identity of the anonymous author. However, had I been more diligent in my research I should have studied other works that have since been brought to my attention, in particular, an article by Arthur Hamilton Smith (Smith) entitled: “Lord Elgin and His Collection”. LINK

Had I read Smith’s article it would have saved me many hours of research to arrive at the same conclusion, namely that Hunt wrote the Memorandum. My disappointment at my superfluous efforts was balanced by amusement at the fact that I had arrived at the correct conclusion, albeit by a circuitous and unnecessary route.

While I believe much of what A. H. Smith revealed, he gilds the lily, and what did he leave out?

Details of my extensive, amateur delving, which arrived at the conclusion that: “Elgin used bogus, anonymous, Memorandums written by himself or his Chaplin/ Occasional Private Secretary, Dr Philip Hunt, to mislead Parliament in support of his petition for the sale of his collection.” can be found in my ‘Elgin Cheated at Marbles’ blog Chapter 4 entitled: ‘Elgin’s bogus Memorandums’ LINK

In short, I reckoned that Elgin, in using these memorandums (which if he didn’t commission or write, he at least knew about) as independent evidence of his acts in Greece to influence parliament, was perpetrating a fraud, and as such he invalidated the basis on which the Elgin Marbles were bought on behalf of the British people.

My conclusions re the author rhymed with Smith’s, who showed that Elgin himself confirms the author of the Memorandum as Hunt, as well as the fact that these memorandums were central to the parliamentary purchase negotiations in a letter to his mother. Smith wrote:

“Philip Hunt had left Athens with Lord Elgin in January, 1803, and had been in his company at Malta. They had separated, and Hunt was travelling in Savoy, when he was arrested under Napoleon’s decree. He was afterwards allowed to join Lord Elgin at Pau, and employed himself drawing up a Memorandum on the operations in Greece. A copy was forwarded by Lord Elgin248to his Mother.

‘His (Hunt’s) detention in France (tho’ thank God, I was not the occasion of it, we were not then travelling together) has been of the greatest disadvantage to him. But he is endeavouring to make of it what use he can, by great application; and I am sure this letter will be considered as a very classical as well as able paper.’

The Memorandum or letter in question was a statement drawn up for the information of Hunt’s patron, Lord Upper Ossory,249and consisted of an account, drawn up from memory, of the operations at Athens. Later on it formed the basis of the Memorandum on the Earl’ of Elgin’s Pursuits in Greece, which was drawn up by Lord Elgin, and played a considerable part in the purchase negotiations.”

So it seems certain that the bulk of the text in the various editions of the Memorandum, which dealt with Elgin’s pursuits in Greece were written by Hunt in France.

What is less certain is the identity of the authors of the latter part of the Memorandum dealing with the public reaction to the exhibition of the Parthenon Marbles at Bloomsbury, London in 1809, that is, when Hunt was no longer on the scene, and of course the amendments to the various memorandums.

Arthur Hamilton Smith can hardly be considered as an impartial commentator.

A health warning should accompany A. H. Smith’s article: “Lord Elgin and His Collection” as it was commissioned by Victor Bruce, the 9th Earl of Elgin and grandson of the marbles man.

As if that were not enough to ensure that the article was a subjective view, the author’s brother, Henry B. Smith, was the former first assistant to Victor Bruce when he was Viceroy of India, as well as being his son in law.

So while it contains many factual references to important documents in the possession of the Elgin family it is written by a member of that family’s brother, so can hardly be described as objective.

What is the significance, if any, of the revisions to the original 1810 Memorandum?

In order to examine this question it was necessary to compare the four editions (that I know of) by converting the text from the printed publications into renderable text documents as follows:

1810 edition printed in Edinburgh by Balfour Kirkwood & Co. LINK

1811 edition printed in Edinburgh by Balfour Kirkwood & Co. LINK

1811 edition printed in London for William Miller. LINK

1815 2nd edition Corrected, printed in London by W. Bulmer and Co. LINK

Then by the use of a Word Comparison tool we can see the extent of the editing between the documents. This produced the following:

The 1810/1811Ed. comparison: LINK

The 1811Ed./1811Lon. comparison, LINK

The 1811Lon./1815 comparison: LINK

N.B. The amended text is in red with strikethrough and the new text is in blue.

A. H. Smith maintains that these changes to the various editions of the Memorandum and in particular, those made by Richard William Hamilton, were minor, simply making “a few corrections to text”.

This is partly true, some of the amendments are simply corrections to spelling, punctuation, or grammatical errors. For example Smith refers to a letter dated Dec 15, 1810 letter from the Earl’s former deputy, Hamilton, to Elgin, in which he tells of how he edited the Memorandum, because he objected strongly to the author’s (Hunt’s) flowery language and gives examples of the words ‘bijou’ and ‘concetto’, which Hamilton had removed.

However there are subtle and not so subtle changes to the various editions, which seem to be more concerned with further concealing Elgin’s devious and immoral actions than with word use. This more substantive editing sought to portray Elgin in the best possible light in the various editions of the Memorandum, when the facts suggested the opposite. This was ‘PR spin’ before that term had been coined.

In a 2008 book entitled “A Century of Spin” authors David Miller & William Dinan examine the power of public relations in the 20th Century, which they say: “is about how corporations invented public relations and used its skills and techniques to impose business interests on public policy and limit the responsiveness of the political system to the preferences and opinions of the masses. The powers of public relations are mysterious in the sense that they are not well known. They are shrouded in secrecy and deception, which often enables PR operatives and PR firms to pursue their objectives undetected.”

If we take Elgin’s sale of his collection to parliament as a business interest then this description might have been written with Elgin’s Memorandums in mind as it describes their PR media role to a tee – more than a century earlier.

My mistakes in assuming the Memorandum detailed events in chronological order would have been shared by parliament in the early 19th Century.

In brief, the Memorandum tells a pretty tale of how Elgin, a lover of the arts with no ulterior motives, was thwarted in his noble ambition to mould, then make casts of architecture and sculptures to inform the arts in Britain. And it was only when he was thwarted in this aim and saw the artefacts he wished to mould and make casts of destroyed, that he decided to remove the originals to a place of safety – England.

This apparent, unfolding story timeline in the memorandums, belies the actual circumstances under which Elgin obtained his collection. I will set out the ‘Facts’ and the ‘Spin’ in a series of examples, which unlike the memorandums will be in chronological order. I will set out my view in a ‘Comment’ and would welcome those of you who read this (rather lengthy) article to comment in the form provided for this purpose.

EXAMPLE 1/ Did Elgin and old friend Thomas Harrison plan the plunder of Greece to decorate Broomhall, or did Elgin simply wish to inform and encourage the arts?

Some surplus building material from Broomhall (red porphyry) was used on the tomb of Robert the Bruce in Dunfermline Abbey.

FACT: It is a matter of record that Elgin pleaded with Lord Grenville, the then Foreign Secretary to be given the post of ambassador to the Ottoman Empire as an equal to Imperial French representatives at the Porte in November 1798, at a time when he would have known that a British fleet, under the command of Admiral Nelson, had destroyed the French navy on August 1, 1798 at the Battle of Aboukir.

That is, Elgin knew the French ambassador (also a collector), Choiseul-Gouffier, had taken a Parthenon metope as well as a piece of the frieze and if he was appointed ambassador he would be in a much stronger position than his French counterpart to have access to similar.

We now know from a letter that Elgin sent to Lusieri on the 10th of July 1801 (with a 14 July post script) that Elgin had plans of his new house at Broomhall drawn up by the architect Thomas Harrison (Harrison) before he left for Greece. LINK

As can be seen from this letter, the detailed drawings made by Harrison included specific designs for the inclusion of heavy imported columns and other ornamental masonry that Elgin intended collecting in Greece. Elgin stressed that he wanted his collectors to have these drawings in mind as they went about their work. He stressed his preference for original “sculptured marble, or historic piece.”

Harrison was no stranger to Elgin; he was a trusted friend since 1796 when Elgin hired him for the Broomhall job. Elgin trusted Harrison as a friend to the extent that he took him with him to Dirleton, when he went there courting his future wife Mary Nisbet.

In effect Elgin had Harrison design his new home at Broomhall specifically to accommodate items he knew of, and intended to acquire, in Greece. Elgin intended to join the many collectors of Greek antiquities like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, another aristocratic collector, who, almost a century earlier took advantage of that country’s distressed state.

Failing to acquire ancient specimens because of their size or other logistical problems like those experienced, and well-documented, by Lady Montagu, Elgin intended to make mouldings of such items from which plaster casts would be made.

We also know that Elgin procured bulk material of great value, such as the app. 3 Tonnes of rare porphyry columns with no decoration, which were shipped out of Constantinople on the brig ‘Salamine’ on about 15 June 1801. On that occassion another piece weighing approximately 1.3 Tonnes had to be left behind to await larger transport as it would have sunk the small brig. LINK

SPIN: The opening paragraph of the four Memorandums portrays the desire to have specimens and casts as being a mere aside arising out of Elgin’s casual encounter with Harrison the architect. It was as if he had met him on the street and Harrison said “oh by the way Elgin old chap, if by chance you get the opportunity to pick up any nice bits of Greek architecture or sculpture, do take it”

The attempt to portray the conversation about the arts with Harrison as an incidental factor when Elgin was building a classical style house and was about to go to the home of classical architecture sticks out like a sore thumb.

200 years before I carried out the above comparison the critic in the “British Review, and London Critical Journal” was mystified as to why the question of Elgin’s dealings with Thomas Harrison were treated as a ‘casualty’ and in fact these opening lines were subject to four revisions in the Memorandum.

However that apart, the critique by the British Review was in no doubt that the general purpose of the publication was to gain public sympathy for Elgin’s sales pitch to parliament.

It is also the case that as well as being a justification for Elgin’s actions the Memorandum was a vehicle for attempting to inflate the value of the various items by exaggerating the time, effort and expense spent in obtaining them. LINK

So in the Memorandum we go from Elgin just “happened to be in much” intercourse with Harrison to the very positive “was in habits of frequent” intercourse.

Elgin’s dissembling has begun at the very beginning. He is making his case that it was never his intention to have regard for anything but the furtherance of understanding of the arts in England, while his actions showed the very opposite intention.

Comment. As a boy living in Rosyth in the early/mid 1950s I spent many a day wandering through the grounds of the nearby Broomhall estate with my friend as we tried to expand our birds-egg collection. Making detours to avoid the gamekeeper, as well as youthful curiosity, sometimes brought us to the perimeter of the mansion and I remember that one area adjacent to the house was like a builder’s yard with slabs of marble and other material, statues, grave-stones, fountains, and all manner of items lying about in disarray.

The actual details from so long ago are hard to describe in detail, but it was a surreal scene with loot, probably from Greece, Turkey, India and China strewn about the Fife home of the descendants of Imperial governors of several continents.

Some of these items were of course the castings made from the moulds made by Balestra and Theodore the Calmouk and I know that some columns and statues of this sort were once offered, free of charge, by the current, 11th Earl of Elgin to the publican of the Elgin Hotel at Charlestown, who was his tenant and then feudal vassal. This kind offer of casts to decorate the lounge in that hotel was declined by the publican.

Other artefacts surplus to the Broomhall’s needs would have been originals, some we know of, since disposed. I also know that at a later date (about 1990) the current Earl of Elgin dragooned a squad of Territorial Army soldiers to get rid of some of his ancestor’s trophies, which were surplus to requirement.

It is a matter of fact that some plunder was taken in the 19th century, not to protect it for the arts, but was stolen to order for use on Harrison’s building project. Simply taken for the type of material it was, or because of its history, and was built into Broomhall, while surplus was discarded or used elsewhere. An example of this is the red porphyry slabs that once formed the base and lid of Constantine’s sarcophagus, some of which is said to be built into Broomhall while the surplus was cut up to decorate the tomb of Robert the Bruce (above) in Dunfermline Abbey. LINK

This porphyry may have been misused by the Ottoman regime (part of it was used as a door sole-plate according to Elgin’s mother in law, Mrs Hamilton Nisbet), but at least it was misused in the proximity of its proper place. It is said that the priceless material later used on Bruce’s tomb was once used as the bases for hen-huts at Broomhall.

Other items that once graced the ‘Broomhall salvage-reclamation yard’ have since been sold, such as the grave steles of Myttion and others which were sold to John Paul Getty for huge sums and now can be seen in Malibou.

It seems clear, to me at least, that had Elgin’s marriage not failed and had he retained the backing and funds of his wealthy father-in-law William Hamilton Nisbet (who financed his Greek tour) when he returned from France, there would have been no sale of marbles to parliament and the empty friezes at Broomhall would now be decorated with the Parthenon marbles that currently lie in the British Museum.

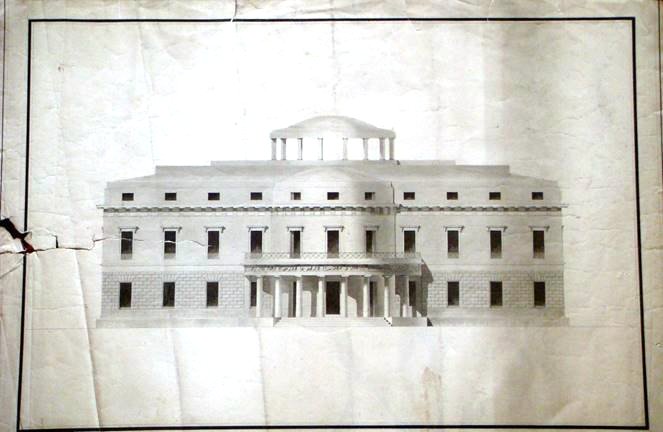

My view of this is supported by the drawings the Elgin family retain of the British Embassy at Pera, which Vincenzo Ballestra copied exactly from Thomas Harrison’s original Broomhall plans.

As can be seen from the Pera drawing it was planned that there would be a large portico with eight columns, decorated with an ornate frieze of carved stone, just like the frieze disinvested from the Parthenon by Hunt’s party Circa 1801.

If Elgin had managed to keep his wife and her father’s financial backing Broomhall would now have a similar portico to that planned for Pera, supported by a Pentelic marble caryatid from the Erechtheion and decorated with the Parthenon frieze; he didn’t, it doesn’t.

EXAMPLE 2/ Did Elgin plot a detour to outdo Montagu, or did he stumble on the Sigean marbles/Boustrophedon by chance and his passing friend gave him permission to take them?

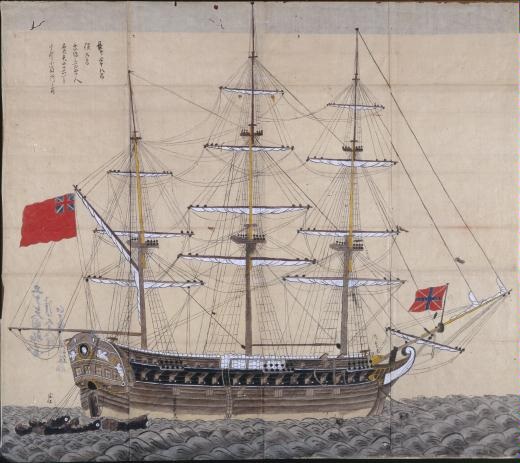

HMS Phaeton, a 38-gun, 280-man frigate, built in Liverpool in 1782

HMS Phaeton, a 38-gun, 280-man frigate, built in Liverpool in 1782

FACT : We now know that Elgin began his collection of ancient sacred relics before he had even arrived at Constantinople to present his credentials as ambassador to the Porte.

It is well documented that HMS Phaeton anchored off the Island of Tenedos in late October 1799 and on the Wednesday 30th October 1799, Lady Mary Bruce, the Countess of Elgin, (Mary Nisbet) went ashore there and visited the Consul and his wife (both Greeks). That same day Elgin and a party left the Phaeton and set off in a Turkish boat and then rode 12 miles inland to “search Troy”.

It is also well recorded by Mary Nisbet that on Friday 1st November 1799, the Phaeton was under way to Constantinople, but stopped at the entrance to the Dardanelles and again Elgin led a party, which left HMS Phaeton by boat, landed near the Promontory of Sigaeum, (Point Janissary) then travelled about 11 miles on horseback to the village of “Sigamon”.

Later Philip Hunt recounts this visit as being when he first viewed the well documented Sigaeum Inscriptions or ‘Boustrophedon’ marbles; two inscribed monuments which sat at either side of the door of St George’s church at the village of Yenicher, on the Plain of Troy.

Elgin’s reconnaissance party consisted of his wife Mary Nisbet, Captain James Nicoll Morris; the master of the Phaeton, Major Fletcher; a member of General Koehler’s staff, Dr. Philip Hunt, Dr. Joseph Dacre Carlyle; all on horseback, and Mary Nisbet’s servant Masterman and other Greek servants on Asses. LINK

After the Elgin party’s visit to Yenicher on the Plain of Troy, they were transported back to the Phaeton from Sigaeum by boat, through a heavy swell. They then continued their journey on the Phaeton, which sailed to the Dardanelles where they arrived on Saturday 2nd November.

Waiting to greet Elgin was the Captain Pasha, a Turkish admiral by the name of Kuchuk Hussein. Also waiting to greet Elgin were General Koehler and his men of the Expeditionary Force aboard a transport ship. According to Dr. William Wittman, a physician with General Koehler the place they were at anchor was near “Chennecally”.

According to Mary Nisbet, HMS Phaeton anchored “alongside of the Captain Pasha’s ship, 132 Guns”

The Captain Pasha, who was commander of the Turkish navy and married to a princess, received Elgin and his wife separately, and with great ceremony showered them with expensive gifts, including a model of his ship studded with diamonds and rubies. Later he feted them together at a meal in Elgin’s honour on his (the Captain Pasha’s) ship, the Sultan Selim, the 1,200 crew flagship of the Ottoman fleet.

At 6 am on Sunday the 3rd of November, the day after they had dined on the Sultan Selim, the Elgins sailed on the Phaeton for Constantinople. Arriving there on Wednesday 6th November they went to their “Palace”, the former residence of the French Ambassador and the following day, Thursday 7th November they attended a ball at the Imperial Minister, Sir Sydney Smith’s residence.

Also on the 7th November, Dr William Wittman with a party of soldiers from General Koehler’s British Expeditionary Force, and a Turk bearing a firman from the Captain Pasha, travelled on horses provided by the local Turkish official to the village of Giawr-keuy or Cape Janissary: “to procure a very curious bas-relief and the celebrated Sigaeum inscription for Lord Elgin, who had seen them and was desirous to transmit them to England”. LINK

On Saturday 9th November the Captain Pasha’s Great Man sent 90 attendants all carrying fruit flowers and other fine gifts for the Elgins in their residence and then the Captain Pasha’s Great Man arrived with another party of servants carrying 8 trays of fine Berlin china dishes full of jams.

Lord Elgin did not formally present his credentials to the Porte in the person of the Kaymacan Pasha (who was acting in the place of the Sultan who was in Syria with his army) at the Topkapi palace until about the 23rd of November 1799, the planned ceremony for the 21st November having been cancelled due to heavy rain.

Three days after Elgin’s presentation to the Kaymacan Pasha (about 27th November 1799) he was eventually brought before the Sultan, by which time the Phaeton was homeward bound, collecting the Sigean marbles at Chennecally where Wittman records her there, outward bound from Constantinople, on the 30th November.

A. H. Smith in an Appendix to his ‘Lord Elgin & his Collection’ puff piece gives a warning that records regarding Elgin’s plunder were complicated and fragmentary, but even he has the Phaeton, as the very first booty vessel, leaving Constantinople for Deptford about 1800? (several months early) with a cargo of “Sigean inscription, statue, pieces of marble“.

SPIN: The Sigean/Boustrophedon marbles event is set out near the end of the Memorandum, as if, in a progressive story, it was the very last treasure collected, when in fact it was the first. The circumstances of the collection of the Boustrophedon are portrayed as if Thomas Bruce (not the influential British ambassador the Earl of Elgin) was wandering on the Plain of Troy and just by happened on it. Then, the later editions (1811 L & 1815) tell a similar story which implies that Elgin’s gift from the Captain Pasha took place at the location where the Boustrophedon was.

The date of this event on the Plain of Troy is kept vague. This means that the reader does not know if it took place on Elgin’s first visit or a subsequent return journey.

The later editions give the impression that he was on the Plain of Troy some time after he had met, and became good friends with, the Captain Pasha, and when Thomas Bruce expressed a liking for the marble, his good friend the Captain gave him permission to remove them.

The first amendments to the 1810 Memorandum in the 1811 Edinburgh Memorandum are aimed at downplaying the desireability of the Boustrophedon Inscription, a large marble stele weighing over one ton in weight, coveted by so many and neither edition makes any mention of the involvement of the Captain Pasha, who of course was not known to Elgin when he first viewed it at Sigeum.

The amendments to the later editions regarding his friendship with the Captain Pasha might have been made to support a letter dated 31 July 1811 from Elgin to the then Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval. In it Elgin states that despite the rumours that are circulating that he had acquired his collection as presents from the Porte, without incurring any personal expense, he has never had any privileges as ambassador except one time at Cape Sigeum, where he was granted sanction to remove the Boustrophedon Inscription and a small Bas-relief by the Captain Pasha “whom I met accidentally on the spot, gave me his sanction to remove, at my own expence” (p 312 Smith). Elgin’s letter of 31 July 1811 to Spencer Perceval actually says he “accidentally met at the spot”, but whichever version is correct he didn’t meet the Captain Pasha until a day later on the 2nd of November, one day after he visited the site of the Boustrophedon, and 30 kilometres away on the Captain Pasha’s ship.

This of course is another example of Elgin lying as evidenced by the independent accounts of William Wittman, Philip Hunt and his wife, Mary Nisbet.

Think on that; lying in writing to the Prime Minister.

Smith further compounds Elgin’s lie on page 182 when he feigns ignorance of when the Boustrophedon was acquired. In this regard he says it was “At some date between Lord Elgin’s arrival and Hunt’s tour in March, 1801, Lord Elgin had become possessed, by the favour of the Sultan and the Capitan Pasha, of two noted monuments from the Church of St. George at Cape Sigeum”. This statement is inaccurate by some 16 months and contradicts his own Appendix of shipping movements, where the Sigean inscription is the first of many cargoes that arrived in British ports in 33 Royal and Merchant naval vessels laden with the ‘collections’ of sculptures acquired by Elgin and his wife. LINK

Comment: Given his capacity for lying, it is doubtful that Elgin found himself, by accident of wind or weather, at Tenedos (not on a direct course to the Dardanelles from his last landfall at the island of Thermia), from where he went ashore. Similarly when his ship was at anchor off the Promontory of Sigaeum.

Nor is it likely that these were anything other than planned, premeditated acts. This much is evidenced by the fact that Major Fletcher had travelled away from the rest of the British Expeditionary Force, which awaited Elgin on a transport alongside the Captain Pasha’s ship at the Dardanelles.

Elgin may have rendezvoused with Major Fletcher for diplomatic/military reasons, but it is also clear that he was searching for the inscribed Sigean marbles which were described in detail, sometimes accompanied by maps, by many classical Greek scholars, travellers and collectors, but most notably by Lady Montagu.

By seeking out the Sigean Marbles with one of General Koehler’s officers they were as good his. Like a purchaser puts his ‘reserved’ card on an item in an auction room Elgin had taken Major Fletcher to the items that he had earmarked as his own.

And Elgin wasn’t going to be beaten by logistics as that Lady was. He had at his disposal, the Royal Navy Mediterranean fleet, plus General Koehler and his 76 strong British Expeditionary Force, who were repairing forts in the area; and they had all the equipment and knowhow to lift and cart the Bostrophedon marbles to Phaeton and onward to Dartford, which they did.

With Napoleon having fled from Egypt after the French defeat at the Battle of the Nile and Britain in favour with Turkey because of that, Elgin was set on taking advantage of the empowerment this gave a British ambassador, for his personal benefit.

This was an example of opportunism at the very onset of Elgin’s embassy, in fact weeks before he even had his credentials accepted by The Porte. No excuses regarding protection of the arts will excuse the despicable act of removing sacred artefacts from a Greek church by force of British arms, in concert with occupation officials and with complete disregard for the protestations of the oppressed local people and their priests.

EXAMPLE 3/ Did the abuse of British Imperial power by threats and lies enable Elgin to pillage and plunder sacred Greek relics, or did he only resort to removing permanent artefacts when he witnessed evidence of their damage and destruction?

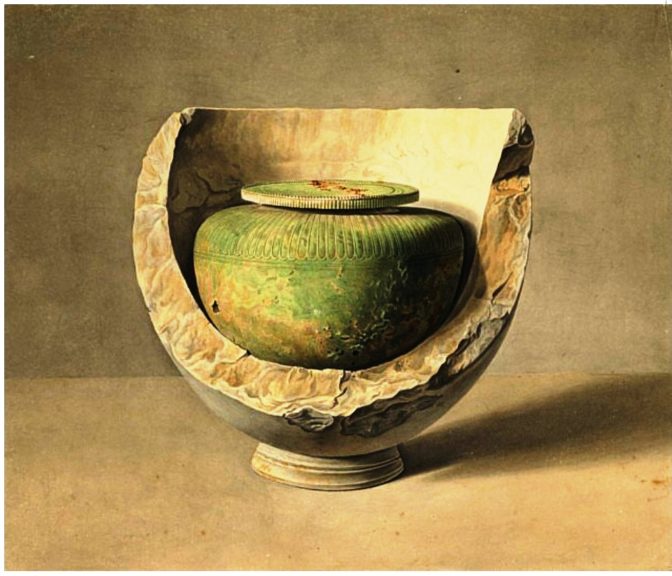

The marble outer urn and the bronze inner urn with lid (later lost) uncovered in the ‘Aspasia’ Tumulus excavation. The urn was probably broken by a sledgehammer, which was the way these burial sites were opened (See Dodwell).

The marble outer urn and the bronze inner urn with lid (later lost) uncovered in the ‘Aspasia’ Tumulus excavation. The urn was probably broken by a sledgehammer, which was the way these burial sites were opened (See Dodwell).

FACT: We know that Elgin through the actions of his party, and Hunt in particular, used violence, or the threat of it, to assist their looting. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than the case of the Disdar of Athens’s son, who Hunt was instrumental in having threatened with being banished as a galley-slave.

Elgin’s artists, delayed by various events didn’t arrive in Athens until 22 July 1800 and Hunt didn’t arrive in Athens from Constantinople till about May 1801, at which time he was put in charge of the artists there. During his brief stay there he saw that the Disdar wasn’t allowing Elgin’s party carte blanche to do as they pleased. And even in their limited actions, they had first to get permission from, then make a payment to, the Disdar.

So Hunt travelled back to Constantinople, arriving on 4th June 1801, the day of Lady Elgin’s birthday ball, and set out the terms for a firman he needed to allow him to do as he saw fit at Athens.

This new firman appears to have been partly granted, (Mary Nisbet writing of it to her father on 9th July 1801 said Pisani, Elgin’s negotiator with the Porte, had “succeeded à merveille” with Elgin’s application), but much more importantly, Hunt was promoted to act as Elgin’s Private Secretary (as the person who held this post, Richard William Hamilton was in Egypt) and given a Mu-Bashir, a Turkish enforcer to see that his wishes are carried out.

In his new role Hunt set off to inspect the forts on the Morea to ensure they were ready, should Napoleon try again to take territory there, and when this was done, the, now emboldened Hunt, called on the Voivode of Athens with Elgin’s letter of application for a new Firman and the resulting document addressed to the Voivode and the Cadi.

Having arrived back in Athens on the evening of July 22, 1801 it can be assumed that he saw the Voivode, the next day. Hunt presented him with Elgin’s letter of application, which was critical of previous mistreatment of Englishmen by the Disdar’s son and the new firman. These presentations, reinforced by Hunt’s “determined tone” and the presence of Raschid Aga, Hunt’s Mu-Bashir, who was superior in rank to the Voivode, enraged the Voivode.

The Disdar’s son (who was then carrying out the last few days of his dying father’s duties) was summoned and after excuses were made that he was not available – which Hunt would not entertain on the basis that he was determined to get to the bottom of the matter of who was to blame for obstructing the English – the boy was eventually brought, trembling and barefooted, before the Voivode.

Hunt pressed his claim that he and other Englishmen had been thwarted in their works at the Parthenon by the officiousness and corrupt practices of the Disdar’s son with such forcefulness that the Voivode pronounced the Disdar’s son was exiled.

Hunt, having had his power with the Voivode demonstrated in this manner, then appealed for clemency on behalf of the Disdar’s son. This plea was accepted by the Voivode and the Cadi, but with a qualification that any second offence by the Disdar’s son against the Englishmen would see him sent to sea as a galley-slave, and of course he would then not inherit his dying father’s office.

As a measure of how Hunt’s bullying had the desired effect, his report of the above meeting to Elgin dated July 31, 1801, simply stated: “The Citadel [The Parthenon as a Turkish military building] is now as open and free to us as the streets of Athens.” LINK

On the same date July 31 the first metope was removed. N.B. This was several months before the French surrender at Alexandria.

Work then proceeded apace in removing the frieze of the Parthenon and other structural marbles to such an extent that on 30 September 1801, Lusieri, Elgin’s artist, who was now more of a disinvestment supervisor, wrote to Elgin expediting his earlier request through Hunt for “a dozen marble saws” and adding his own request for an additional: “three or four, twenty feet in length,”.

Hunt knew that what he was doing was sacrilegious and admitted as much when he asked Elgin’s permission to tell his sponsor Lord Upper Ossory about his role, stating to him in a letter of 21 August 1801 “I know there are envious people who will not fail to represent what has been done here as a violence to the fine remains of Grecian sculpture”

Hunt would not need to be told how wrong his actions were, but he was told, by Thomas Lacey a captain in the Royal Engineers. Lacey, unhappy to be quartered in Egypt wrote to Hunt on 8 October 1801 [Hunt papers] about Elgin commandeering him to assist in Athens, about which he stated: “Congratulate me. I have found a way to escape from the mission. In two days I embark for Athens to plunder temples and commit sacrilege. A proper finish to my career“.

SPIN: In the ever changing text of the memorandums there are three notable phrases that are constants. The first is the paragraph beginning “Under these circumstances” preceding which are various, often non attributable and unproven anecdotes about the destruction of works of art and architecture on the Acropolis; mainly on the Parthenon.

The second phrase follows shortly after the first in the memorandums coming after an anecdote about the failure of a rope while lowering a metope in the period before Elgin’s embassy, when the French held sway, and is “Accentuated by these inducements”. Something Elgin could have had no first-hand knowledge of.

The third phrase that is designed to give the impression that it comes from a lover of the arts who is distraught by the vandalism carried out by others, past and present is the anguished cry “Then and only then did he/Lord Elgin employ means to rescue what still remained from/exposed to a similar fate.”

This plea in mitigation of Elgin’s actions was made, it is said, after he had purchased a second house from a Turk at the portico of the Parthenon, which he demolished and carried out extensive excavations on the ground where it had stood, to no avail (unlike how he had done, with great success, to another house he bought then demolished near the portico at the opposite end), only then to be told by the former owner that the marble treasures that had been dislodged from the portico and fell on the site where the house was built, had been utilised as a building aid; pounded to dust and used as a component in cement mortar.

Elgin gave the same account to the Select Committee of parliament on 29 February 1816 when he stated: “I was obliged to send from Athens to Constantinople for permission to remove a house….I excavated down to the rock, and that without finding anything, when the Turk to whom the house belonged came to me, and laughingly told me, that they were made into the mortar with which he built his house.”

Comment: Mary Nisbet’s letters of 1802 reveal: “We sailed from Constantinople monday evening the 28th of March”, & later in the same letter she states: “It was between 8 and 9 O’clock when we arrived in Athens“(3rd April 1802). LINK

It is also a matter of record that the same lady records leaving Athens for Piraeus with her husband between 11 and 12 o’clock on Tuesday 15 June 1802 and being taken out by boat to embark on HMS Narcissus, which sailed two hours later, on the morning of Wednesday 16 June 1802 for Constantinople via Marathon, Delos and the Dardanelles.

So Lord Elgin’s claim “Then and only then” in his evidence to parliament and his Memorandum, that he only began his disinvestment of the Parthenon after the Old Turk spoke to him, must have been between these dates (3 April & 16 June), say, in May 1802.

As a matter of fact, by May 1802 the vast majority of the Parthenon marbles had been removed and a dozen ships (the current Earl stated in a press article entitled “Romantic Story of the Famous Elgin Marbles” that 22 ships had been involved in removing his ancestor’s plunder) had carried most of it out of Athens. So it is self evident that Elgin lied to parliament on this matter and the accounts in the various memorandums are a fantasy designed to fool a sceptical parliament and public.

EXAMPLE 4/ Was Elgin’s portrayal of an authoritarian and cruel Turkish regime, hostile to, and lording it over the English accurate, or was the opposite the case?

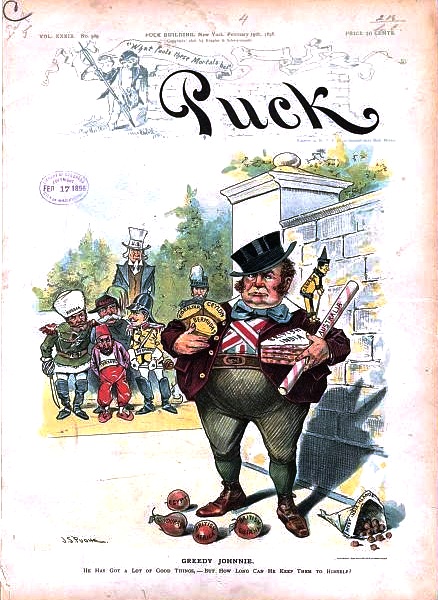

He has got a lot of good things – but how long can he keep them to himself?

FACT: We know that Elgin fully exploited the fact that Great Britain had defeated France in the Battle of The Nile on August 1, 1798 and this placed him in a position of great power when he took up his post. So much so that even before he arrived in Constantinople to present his credentials he procured the Boustrophedon, something the French at the height of their power and influence with the Porte had failed to do.

After The Battle of the Nile ‘Britannia’ ruled the waves of the Mediterranean Sea and Napoleon was lucky to be able to scurry back to France, in so doing crossing the path of Elgin who was on his way to Sicily. With British sea-power came dominance of the Middle East and the Turkish Ottoman Empire valued their new and powerful ally and were overwhelmingly grateful and demonstrably generous to Britain and her subjects.

Elgin in return was churlish and bullying and he humiliated his host, Sultan Selim III in his own capital Constantinople.

The best example of this was when Elgin demanded four specific pieces of porphyry, one of which (the lid and base of Constantine’s sarcophagus) was inside the Nur-u Osmaniye Mosque in Constantinople. Unable to accede to Elgin’s demands the Sultan offered Elgin another piece of valuable porphyry which Elgin took from the servant who brought this gift and threw out of an open window without deigning to look at it proclaiming: “he would have all or none, &. that since they knew how to refuse him such a trifle as a few bits of Red Stone he would take the hint upon the many various favours they were just now asking him!!!”

Elgin would later have his wish when the Sultan reached a face-saving, but humiliating compromise whereby the sarcophagus porphyry that Elgin was demanding was moved from the Sultan’s mosque to a place within his palace, from where its removal by Elgin’s party would not cause a major problem.

All of Elgin’s porphyry was taken home for him by ships of the Royal Navy, the last of it leaving on board HMS Niger. LINK

There is little doubt but that the Ottoman regime was a cruel one, but their generosity and kindness to the representatives of a bigger and more ruthless Imperial power (Great Britain), is self-evident from the letters of Mary Nisbet, Wittman, or whoever else chronicled their travels there at this time.

SPIN: According to the Memorandums the ignorant Turks would climb up and deface sculptures on the Acropolis or break open statues in the hope of finding some hidden treasures. The Turks are categorised by their barbarism and any knowledge of the arts which had been gained by Britain had been in spite of the prejudices and jealousies of the Turks.

Elgin’s artists were on a daily basis mortified by witnessing the Turk’s, acting out of mischief and avarice, carry out the wilful devastation of sculptures and architecture alike.

Elgin’s evidence to the Select Committee if anything was worse than the Memorandum that supported his petition. Elgin stated that in the midsummer of 1801 the attitude of the Ottoman Turkish government changed and they became more amenable, but this is at odds with his earlier removal of the Sigean Marble (refused to the French because of Turks enmity to Christian dogs according to Elgin), which had taken place with the help of the Turkish government on the request of a stranger, almost two years earlier. Most of the Parthenon frieze, metopes etc. had also been removed before Elgin’s midsummer 1801 date.

Comment: The evidence of Wittman in which he told of the theft of 120 Piastres (about £9) on board the ship that carried the British Expeditionary Force to greet Lord Elgin on his arrival in November 1799 belies Elgin’s claims of the Turks only changing their attitude after the defeat of the French land forces (at Alexandria on 2 September 1801).

Wittman tells that a theft of money on the troop transport ship on 5 November 1799 was reported to the Captain Pasha, who was prepared to kill by strangulation the Turkish marine (galangis) a British army officer suspected of having taken it, on the basis that “he was certain an Englishman would never tell an untruth”.

The letters of Elgin’s wife and the chronicles of others are in complete contradiction to the supposed enmity felt by the Turks portrayed in the Memorandums and letters/evidence of Lord Elgin. This myth may have helped Elgin sell his trophies to a sceptical parliament, but the facts say otherwise and the evidence of Elgin’s bullying Sultan Selim III, with regard to the porphyry from the tomb of Constantine the Great is conclusive of the subservience of the Sultan to our bombastic ambassador.

The theft reported by Wittman gives another insight as to how the Turks were afraid to offend the English, and is similar in character to Hunt’s description of how the Disdar’s son was to be exiled as a galley-slave if he didn’t defer to the English.

EXAMPLE 5/ The Memorandums tell of matters that were beyond their ken.

The gold ‘wreath’ or ‘sprig’ from the Tumulus outside Piraeus bought by the British Museum from the Elgin collection in 1960 and reproduced here by kind permission of the BM Free Image service.

FACT: The memorandums give almost identical accounts of how a tumulus (thought to be possibly that of Aspasia) was opened in the presence of Lord and Lady Elgin. This much may have been true, but the impression given is that not only were the Elgin’s there when the tomb was opened, but that they saw the contents that were unearthed from it. The passage reads:

“A tumulus, into which an excavation was commenced under Lord Elgin’s eye during his residence in Athens, has furnished a most valuable treasure of this kind. It consists of a large marble vase, five feet in circumference, inclosing one of bronze thirteen inches in diameter, of beautiful sculpture, in which a deposit of burnt bones, and a lachrymatory of alabaster, of exquisite form; and on the bones lay a wreath of myrtle in gold, having beside leaves, both buds and flowers. The position of this tumulus is on the road that leads from the Port Piraeus to the Salaminian Ferry and Eleusis. May it not be the tomb of Aspasia?”

From Williams, Smith et al, I learned that in fact the gold wreath from the ‘Aspasia’ tumulus site that Elgin and his wife had seen opened, or commenced in 1802, was not unearthed by Lusieri until 1804, at a time when Elgin, his wife and Hunt were under arrest in Pau, France.

But more surprisingly I learned that what was unearthed was not a wreath at all according to Lusieri, who on discovering it in 1804, wrote to Elgin describing it as: “a branch of myrtle, of gold”

There is more confusion about this gold myrtle artefact, which was supposed to have been taken by Lusieri to Malta on the Hydra which sailed from Piraeus on 22nd April 1811with the last of the Parthenon marbles. Lusieri was accompanied on this voyage by Byron and it is assumed he deposited the wreath at Malta together with the marbles all of which would then be shipped on to England.

Valetta harbour in Malta was at that time the lazarette port where all persons or goods from the Levant were quarantined pending clearance before onward transit to European ports.

However Lusieri returned to Athens in July of 1811 and some time later in September 1811 he wrote to Elgin saying that the inner bronze urn in which it had been found was at Malta, but he had: “the little gold spray of myrtle that was in it here. The person who stole it was so kind as to sell it to me.”

So when Hunt had been waxing lyrical in his letters and Elgin’s Memorandums about a gold wreath of myrtle etc., he had not even seen the artefact in question, and probably never did see it. Nor had William Richard Hamilton or indeed Elgin seen it when the Memorandums were published, as it only came into Elgin’s hands in 1825, that is some four years after Lusieri’s death, and even then in dubious circumstances.

This is my understanding of how Elgin came to own it: In 1820 Lusieri, was still at Athens even though in January 1819 Elgin had served him with notice that his contract terminated at the end of that year.

This caused Elgin a problem, because Lusieri retained many valuable artefacts at Athens that he thought belonged to him.

So on October 15th 1820, Elgin wrote to his former secretary, William Richard Hamilton, who was Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs at Naples seeking his help, he explained that Lusieri’s had been given notice of his contract terminating, before stating that he was very keen to get his hands on Lusieri’s drawings and paintings and other artefacts: “especially the golden wreath of myrtle, found in the vase, in Aspasia’s Tumulus“.

Hamilton was later able to help his old friend in this request, and after Lusieri died in 1821 he had Lusieri’s personal possessions, consisting of two boxes and a tin case which had been in the care of the harbour master at Valetta sent, aboard H.M.S. Cambrian, to his offices at Naples.

In 1822 Hamilton was elevated to the post of Minister and Envoy Plenipotentiary at the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and it would appear that he was in that position at Naples when he confiscated the gold myrtle wreath from Lusieri’s boxes on the basis that it was the property of Lord Elgin. Hamilton reached agreement with Lusieri’s heirs in February 1824 on the remaining contents.

Lusieri would seem to have planned to keep the gold myrtle spray as his own (who could blame him?), and, as he hadn’t been paid for some time, he may have had just cause to retain the gold spray as well as his oil paintings and sketches in lieu of unpaid wages.

SPIN: The Memorandum that supported Elgin’s petition to parliament gave an impression of events that were fanciful exaggerations of events bordering on and including downright lies.

In this example the narrative gives an impression of definite events witnessed by Lord Elgin when in fact that main item in question, the gold wreath, was not in fact a wreath, but little more than a sprig when it came into Lord Elgin’s possession some time after 1824.

A gold sprig that Elgin’s descendants sold to the British Museum in 1960.

Comment: The parliamentary committee which examined Lord Elgin’s acquisition of the Parthenon Marbles and other artefacts were not to know of the above events, which in 1816 had still to unfold and they may have believed the Memorandum and taken it at face value.

Had they been appraised of the actual events in this instance they may have questioned Elgin on it and found he was relying on a tissue of lies and second-hand rumour and if he was prepared to play fast and loose with the truth in this instance what else in his Memorandum could be believed?

Summary: I cannot for the life of me understand how any credibility is given to Elgin, Mary Nisbet, Hunt, or the Hamilton Nisbets in their accounts of events in Turkey and Greece.

It is a matter of fact that with regard to the belongings of John Tweddle (the young artist who died in Greece) all of these people were found to have lied in denying they had wrongfully acquired his property (material & intellectual). When the opposite proved to be the case they were found to be liars and thieves of the worst sort.

This caused Mr Hamilton Nisbet to return Tweddle’s goods given to him by Elgin, and Hunt to admit that he used Tweddles writing, passing it off as his own. LINK

The lies in the Memorandum and evidence before the Select Committee are manifold and I can’t believe a word of them, though there must be times when they are describing some truths.

I am astonished that intellectuals such as St Clair and even the cynical Hitchens, can give the dramatis personae, this shabby cast of characters, particularly Elgin, the benefit of the doubt, but they do:

St Clair at p 127, “Elgin himself, with his respect for the old-fashioned codes of honour”; p 129, “Elgin still clung to his ambition to improve the modern art of Great Britain by making examples of the best ancient art accessible to artists”, and p 131 “This parole was never rescinded and Elgin, ever true to the principles of noblesse oblige, regarded himself bound to it right up to the moment of Napoleon’s downfall.”

Hitchens at p 27, “Up to this point, [April 1801] it is important to remember, Lord Elgin’s declared plan was to do no more than make copies and representations, and perhaps collect a few scattered specimens. But, as he was later to tell the House of Commons, his whole design altered at some point in May 1801:”, and p 33 “But the story of ‘the old Turk’ (which we have no reason to doubt) is given as occurring in May 1802. And the first panels were removed from the Parthenon in July 1801.”

St Clair and Hitchens both know that Elgin lied about a series of important matters, but for all that, they still accord him credibility. Hitchens has ‘no reason to doubt’ the proven liar, and St. Clair accords the ‘noblest of motives’ to that same liar and thief.

I take the opposite view and view every statement Elgin and Hunt say with doubt and suspicion.

How anyone can attribute noble motives to a man who in 1807 and 1808 sued his former wife’s partner and soon-to-be husband, William Ferguson, for “Criminal Conversation with the Plaintiff’s wife”, that is, causing his wife to commit adultery some six or seven years previously, is beyond me.

The civil action for this involved having his ex-wife’s love letters to him and all other personal details of her affairs, with him, and then her lover/future husband, Ferguson dragged through a jury court in Scotland and one in England for a damages claim of £20,000, for which a jury awarded him £10,000. LINK

Then, almost two decades later, the money-grabbing Earl, not content with these two awards returned to the courts following the death of his former father-in-law to claim the rents from the departed’s Belhaven estate for his son, or for £10,000 for himself on the basis that his ex-wife as an adulterer was in the eyes of Roman law dead! This court action in 1826 was rejected by a Lord Ordinary at the Court of Session, but Elgin appealed his decision, only for his greedy money-grabbing ploy to again be rejected as groundless by three Court of Session, Appeal Court, Law Lords in 1827. LINK

The term the Noble 7th Earl of Elgin is an oxymoron.

As for Mary Nisbet, (Lady Elgin) her lies are kept from the public eye and one only has to compare the letters which were edited by her great grandson, Lieutenant-Colonel John Patrick Nisbet Hamilton Grant in 1926 before publication, with the actual letters she wrote which are with the British Museum (who seem reluctant to allow me to have copies) and one can see how her descendents and it seems the British Museum have connived to keep the truth of her and her relatives atrocious actions from the public.

I don’t know what regiment the Lieutenant-Colonel (Motto: “Leges juraque serva” = He maintains the laws and his rights) belonged to, but he was certainly acting as a guardsman for the reputation of his Nisbet ancestors, the British diplomatic service and of course the British Museum in his injudicious editing.

From the glimpse Dyfri Williams gives us of the arrogance and greed of Elgin and Mary Nisbet in Constantinople, the British Museum would seem to have good reason to keep the public in the dark about the Letters of Mary Nisbet, but what about our, the public’s rights, to see these documents? LINK

Of course the two gentlemen authors I criticise had been privileged to view the papers of the Elgin family at Broomhall and are both grateful to the current Earl (who is apparently a charming man I would get on well with according to quite a few friends of mine who know him well) and perhaps they feel an obligation to go easy on their friend and host’s ancestor and his accomplices.

I am under no such constraints (and I’m not angling for a knighthood, which might make me spare the actions of one of Her Brittanic Majesty’s Ambassadors of yore) so I think that my assessment is the fairer for that, albeit I do rely on second hand evidence of those letters the Elgin family do make available. I don’t think for a moment they give researchers the full collection. Like the 170 letters and documents of Mary Nisbet held by the British Museum the damning ones in the Elgin family archives will be kept well away from the prying eyes of the likes of St. Clair and Hitchens.

Please feel free to comment on my Memorandum musings and give me some more examples of contradictions in them. My four are but the most obvious to me.

N.B. With other blog commitments a garden and grandchildren to tend to, this effort to mark the bi-centenary of parliaments purchase of the ‘Elgin Marbles’ <sic> may have errors and is still a work in progress, which I will update/edit as and when I can.

Kind regards to anyone who reaches this far. Tom Minogue 09/09/2016

Update 13 Oct 2016. I have received the photos of Mary Nisbet’s letter of 14/15 June 1801 from the British Museum,which among other things show how Elgin, her husband, had “coaxed and bullied Old Selim” and I will update this post with full details shortly.

11/11/2016 See update re BM at Does Mary Nisbet – Lady Elgin – Deserve Brickbats or Bouquets?